Let’s back up several steps and discuss the basics of health insurance in the U.S. There is too much to cover in one blog post, but here is an overview.

Sources of Insurance: Public and Private

Most individuals (91%) had some type of health insurance coverage during the year in 2015 (the most recent data available). Only 9% were uninsured for the entire year. Sixty-seven percent had private insurance – insurance sponsored by a state-licensed health insurer or a self-funded employee health benefit plan; and 37% had public insurance – insurance sponsored by the government. The percentages do not add up to 100% because a number of individuals, especially the elderly, had both private and public insurance.

The federal government, state governments, and local and city governments sponsor public insurance plans, but the largest plans are Medicaid, the program for the poor and disabled; Medicare, the program for the elderly and disabled; and military health care plans.

The privately insured have two options for coverage – group (employment-based) or individual (direct purchase) coverage. Individuals purchase group insurance through their job, or direct purchase insurance through a broker or through their state’s “Obamacare” marketplace/exchange. Both types of policies can cover single individuals, couples, or families.

The figure below summarizes the distribution of health insurance coverage among individuals in 2015.

Types of Plans

Private health insurers offer several different types of plans. The most common is also the least restrictive, a preferred provider organization (PPO), which offers consumers a large network of providers (hospitals, doctors, laboratories, imaging facilities, etc.), pays for care outside of the network (though at a less generous rate), and does not generally require referrals for specialty care.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the most restrictive type of plan, a health maintenance organization (HMO). Why would someone choose a restrictive plan? An HMO generally offers a lower premium (the monthly cost of belonging to the plan) in exchange for a smaller network of providers, refusing to pay for care outside of the network, and requiring referrals for specialty care from a primary care gatekeeper.

In between these two types of plans, in terms of restrictiveness, is the point-of-service (POS) plan. POS plans combine features of both PPOs and HMOs, generally requiring referrals for specialty care, but paying for care outside of the provider network. Like PPOs, these plans also tend to have wide provider networks.

An exclusive provider organization (EPO) also lies somewhere between a PPO and an HMO, but is more restrictive than a POS plan. Like HMOs, these plans have narrow provider networks and limited, if any, out-of-network benefits (i.e., the plan will generally not pay for care outside of the network). Unlike an HMO, however, EPOs usually do not require referrals for specialty care from a primary care gatekeeper.

An increasingly common type of plan – in fact, now the second most common after a PPO – is a high deductible health plan (HDHP). I have discussed these plans and their associated savings options – for example, health savings accounts – in a previous post.

It is worth noting that the lines between all of these plans can blur, and that they tend to share the same features. All of the above can be categorized under managed care plans. There still exist non-managed care plans, called conventional or indemnity plans, though these are increasingly rare. Indemnity plans generally pay a fixed amount per hospital day or episode to the patient (rather than to the provider). There are managed indemnity plans as well, but these, too, are rare.

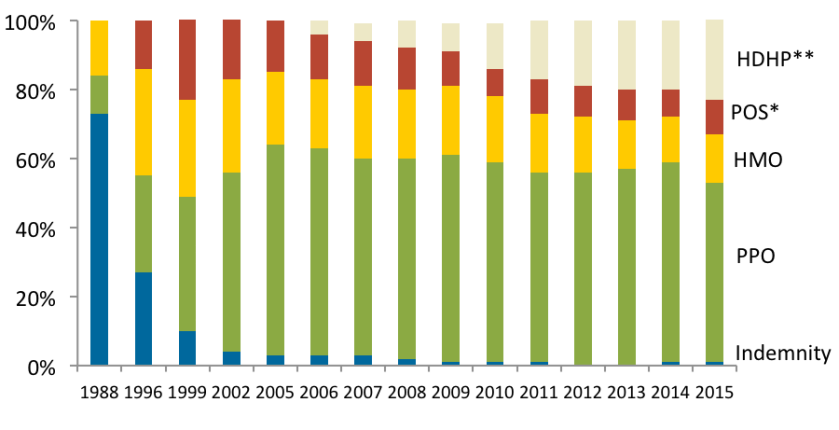

The figure below illustrates the trend in group (employment-based) health insurance plans since the 1980s. The survey did not ask about EPOs, which are a newer product, and it did not ask about HDHPs until 2006. As shown, indemnity plans are increasingly rare, and HDHPs are on the rise, though PPOs are still the most popular. The HMO “heyday” was in the late 1990s, and now are less popular.

*POS plans not separately identified in 1988

**Survey did not begin asking about HDHP plans until 2006

Strictly speaking, public insurers are not managed care plans because they do not negotiate with a network of providers for a discounted rate; rather, they set an administrative rate. Increasingly, however, public insurers contract with private insurers to offer beneficiaries the option to enroll in managed care plans. For example, one-third of Medicare beneficiaries have elected to forgo traditional “fee-for-service” Medicare and instead have enrolled in private Medicare Advantage (Medicare Part C) plans. Medicare Advantage plans may be HMOs, PPOs, or any other type of managed care plan. And all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut, and Wyoming – offer or require managed care for Medicaid enrollees.

Cost-sharing

Most private and Medicare plans share similar cost-sharing features. Cost-sharing can refer to the amount that you must pay out-of-pocket, or the amount that your plan must pay out of pocket, because together, you share in the costs of your care. Pay attention to the language that your plan uses so that you do not get confused about who is sharing in what costs. In general, there is a tradeoff between generosity of benefits (low cost-sharing, large network of providers) and a low premium.

The same cost-sharing features can be found in most plans – public or private. A deductible is the amount that you must pay before your health insurance coverage pays for any care at all. For example, you might be required to pay $500 before your insurance pays for care. The deductible is usually higher for a family plan than for an single plan. What distinguishes an HDHP from other plans is just that the deductible is very high, and that HDHPs may be paired with savings options such as health savings accounts. Not all care is subject to the deductible; for example, your insurer may cover preventive visits even before you have paid your deductible.

A copayment (copay) is a flat fee per visit, hospital stay, or other episode of care. For example, you might have a $20 copayment for a physician office visit, or a $300 copayment for an inpatient hospitalization. Coinsurance is a fee that is a percentage of the price of the visit; for example, 20% of the price of an ambulatory surgery or 50% of the price of a brand-name drug. Note that hospitalizations generally have two separate fees – the facility fee and the physician (professional) fee, so the price of a hospitalization is the combination of the two.

An out-of-pocket limit or stop-loss is the amount that you must pay before your insurance covers 100% of your expenses.

Some, but not all, health plans also cover outpatient prescription drugs. All health plans in the state health insurance exchanges must cover prescription drugs. A formulary is a list of covered drugs. A closed formulary means that the plan will not pay for drugs not listed on the formulary (much like an HMO will not pay for care outside of the provider network), while an open formulary means that the plan will pay for drugs not listed, but at a lower rate (much like a PPO will pay for care outside of the provider network, but at a lower rate). Formularies usually have tiers, with lower tiers corresponding to lower rates of cost-sharing for the enrollee. For example, drugs in tier 1 might be generic drugs, drugs in tier 2 might be preferred brand-name drugs for which the insurer can obtain a discounted rate, drugs in tier 3 might be non-preferred brand name drugs, and drugs in tier 4 might be biologic drugs that can only be administered in a doctor’s office. Like provider networks and cost-sharing structures among health plans, formularies vary widely among drug plans.

For more definitions, and a cost-sharing example, go to healthcare.gov’s Glossary of Health Coverage and Medical Terms.